The Un-Making Of Madness

Posted on Jul 23, 2024 in Blog | 0 comments

Here’s the latest installment in my sporadically produced interactions with writers whose works I admire. I present here, David Fitzpatrick’s dazzling new work.

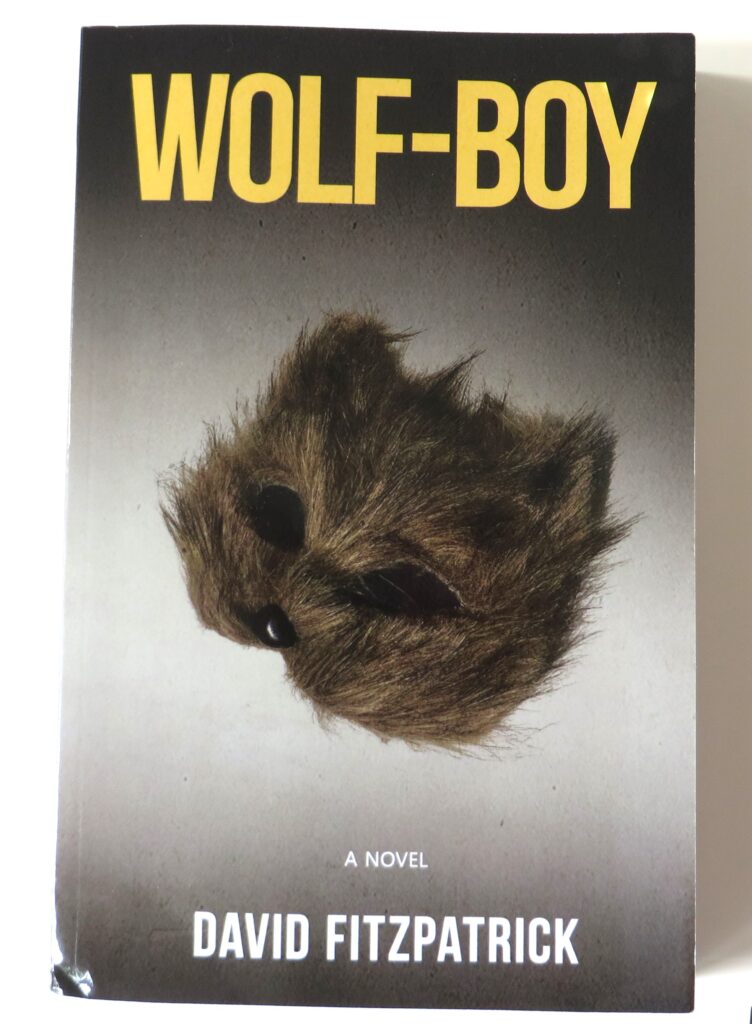

In his just released first novel, Wolf-Boy, Running Wild Press, July 2024, David Fitzpatrick exemplifies the oft quoted writer’s directive to “write what you know.” While that’s an ambiguous task that can encompass an enormous expanse of experience, in Fitzpatrick’s case, he writes about life crumbling from the inside out and reassembling it from the shattered pieces. In fierce prose the author leads us into a teenage boy’s forbidden and dangerous world of sexual adventurism fueled by naiveité and drugs.

If everything in life is a setup, then Fitzpatrick’s protagonist never stood a chance against one summer’s swirl of fate or the young woman, only twenty-one herself, who, with their sidekick Liam, seduces young Danny into wanton debauchery and eventually a psychiatric hospital. The author, whose previously published memoir, Sharp: My Story of Madness, Cutting, and How I Reclaimed My Life, is an intimate exploration of his own years propelled by mental illness and how he emerged to write about it. So it makes sense that his first novel would take some of the same themes in his own life and twist them into an unpredictable new set of complex fictional situations.

With Wolf-Boy, Fitzpatrick joins the pantheon of writers whose works explore madness and the places that treat it from Ken Kesey who based One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest on his experiences as an orderly on a psychiatric ward to Wally Lamb’s I Know This Much Is True and Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar to list but a few. With the entry of Wolf-Boy Fitzpatrick adds a surprise twist as Danny gets sucked into a world where boy meets girl meets boy meets girl and round and round they go until Danny no longer knows who he is or what he wants, in the process losing control of the real world around him and sinking into a maelstrom of – not depravity – but a construct created by Gracie, the girl photographer who uses her lens as a means to entice her two boy toys into a kind of living art work of her creation.

Serious questions of sexual identity and the autonomy to make decisions about what to accept as reasonable – even healthy – choices, emerge as the author takes us through one summer on Cape Cod when Danny comes of age willingly led by the charismatic, voluptuous Gracie who weaponizes her camera to record their masked journey. As Gracie’s photographs of the underage boys take on legally questionable imagery, she insists on masking her subjects with Danny as the eponymous Wolf-Boy.

After getting his MFA in 2011 from Fairfield University’s program situated on tiny, idyllic Enders Island off the Connecticut coast near the old whaling port of Mystic, Fitzpatrick, after a mighty struggle to rebuild the wreckage of his life, began writing seriously. His resulting memoir of crushing years of mental illness detailed that journey. But then, turning to fiction, he began another long journey into unchartered territory. Somewhere within the twelve years writing his first LGBTQ coming of age novel, Fitzpatrick found his direction. Writing may be a solitary occupation but it also involves a lot of input and advice.

At a lunch with his agent after the memoir had been published to critical acclaim, Fitzpatrick recalls in a slow, deep voice, as if reliving the moment through a thick fog, “He said, ‘David, you write really well about Cape Cod in the summer and families. Why don’t you do something there?’ So I thought, huh. But then he said, ‘Just take this incredible woman who’s very seductive and operates with stealth and give her a camera.’ And I said, maybe she’s artsy, a Yale dropout, a photographer named Gracie Rose.”

Fitzpatrick explains, “I just couldn’t get the focus on mental health out of my head so my characters were always influenced by it. For years I had one version of the book called Gracie and my agent sent it to the big New York publishers and one wrote back to my agent, ‘I’m sorry it’s not going to work for us but let me tell you, I would buy this book for myself with my own money and read it because it’s such a fascinating work.’ I couldn’t get over that comment and it took the air out of my sails.” Another editor, this time with a publisher that did find the book worked, suggested a change of focus.

As Fitzpatrick recalls, “My editor said, ‘I think we have to change it because I have to tell you people are not going to be sympathetic to Gracie or to your other characters because Danny puts himself down so much for his bisexual feelings toward Liam.”

As for the author, he’s surprised by one thing. “After twelve years of getting rejected,” he says, “it’s surprising just to have the actual book in my hands. I rewrote the story over that time having four or five different versions when it was called Gracie.”

And that one comment shifted the focus for Fitzpatrick making Danny the book’s protagonist and his struggles with self discovery leading to disintegration fueled the story turning Gracie, the seductress with a camera into the opposite of an anti hero – perhaps an anti villain. Because all the characters in Wolf-Boy are multidimensional and none of them are all evil or all good, the story follows how people can come apart but also be put back together. While the author says that the character Danny is not the person he was in his memoir, Sharp, there are parallels. A teenage boy who doesn’t yet know how his body works being enticed into experiences he can’t control and then the boy himself spins out of control while those who precipitated his unraveling – especially the seductress Gracie – simply move on to seducing an ever widening audience of devoted followers.

There’s resonance in such a theme as we know how easily people can be seduced and duped into following false gods and goddesses. If you sense a biblical theme as well, you’re not far off since the trio of Danny, Gracie and Liam in Wolf-Boy practice their rites and rituals in a giant tree house – a coming of age Eden removed from the real world.

Fitzpatrick’s next novel arrived with more speed. An LBGTQ thriller, End Zone, is already in the publishing pipeline, due out in April, 2025.

It’s been said in Hollywood that no one ever sets out to make a bad movie. For writers that resonates. “I start a book hoping it will be good,” says Fitzpatrick. “I think I have the confidence that there will be redemption by the end of the story.”

The process of writing hopefully will be as redemptive for the reader as it must be for the author.